what softness makes possible

on giving form to ideas, making spaces to meet each other, and going beyond gestures...

I’m sitting on the ground, covered in dust, sweat rolling down my back. I tip a paper cup of sand into the mouth of a vase. Seven cups each, to steady them against the northeast winds. Over 100 vases sit in front of me, waiting their turn.

I pick up a vase etched with waves and remember the woman’s words: the Matsuese spirit is like the sea: unyielding, unbroken. For 21 years, bombs pounded these islands on every odd-numbered day. And still, on the even days, the people rose: mending bodies, patching homes, refusing to let themselves be shattered. I pour in seven cups of sand.

I lift another vase, painted with the 彼岸花 (red spider lily). The elder who drew it said this flower, which blooms from barren ground, embodies the Matsu spirit. I fill it, too, with seven cups. With each story, my heart swells. Every pour feels sacred.

Years ago, a designer on my team quit in the middle of a major health policy project. “I want to build a health clinic with my hands,” she told me. I was incredulous: we were fighting for national reforms, shaping the entire health care system. And she wanted to build… a clinic?

But now, filling these vases, I finally understand. Policy lives in abstraction. Human needs are tabulated into statistics and indignities ranked by scale, until only the grossest violations of the human spirit are deemed worthy of attention. When negotiating legislative demands or program designs, you justify the compromises: this cut will exclude that mother you spent an afternoon consoling, that decision undermines the most vulnerable—but we can’t serve everybody. You see the harm abstraction hides; it haunts you. And still, you go along—for the greater good, you tell yourself.

After 15 years, I needed another scale. Things I could touch. Moments of intimacy. Alignment in every decision.

I never planned to make art, but my facilitation practice has always been in service of tending to and shifting relationships. In recent months, I’ve been exploring how material presence—through installations, offerings, rituals—changes the texture of dialogue and opens new possibilities between us.

Beyond my own experiments, I’ve come to believe our way out of these polycrises lies in centering the imagination of artists. Policy is dominated by lawyers and economists—professions trained to narrow, not expand, possibility. (Shout out to those who resist the mold: Julian Aguon, Chase Strangio, Michelle Kuo, and many more.) Lawyers, for the most part, tell us what we can’t do. Economists model the world on shaky assumptions they themselves admit don’t hold. Why are these the people in charge?

It reflects a false hierarchy of importance: lawyers and economists are assumed essential, while artists are treated as ornamental—tucked away in the “culture” corner instead of at the center of how we make decisions. I saw this dynamic up close in Bengaluru in 2024, at a gathering hosted by a health-policy foundation that also funded the arts. The arts team was pressed to justify their impact in policy terms: What change did it spark in Brussels? How many minds did it shift?

As facilitator, I let the group wrestle with the questions, but the power dynamics were clear: those who “make real change” carried more weight. Then I claimed facilitator’s prerogative: this obsession with measuring and extracting “impact” echoes the logics of capitalism and colonization. It reduces everything—humans, land, spirit—to outputs, wringing us dry until nothing remains but exhaustion. Measurement itself is a form of violence. It admits only what can be rendered as data, casting aside all that resists capture: wonder, longing, grief, joy, tenderness, spirit, solidarity, the sacred.

So what would it mean to center the visions of those trained to hold a wider imagination? To build infrastructure rooted in practices where—even if just for the span of an exhibition or even an activation—consensus reality is suspended and we practice other ways of being?

I was captivated enough by these questions to begin advocating for them in talks, even joining a few boards—an arts organization, a deliberative democracy nonprofit, and a think tank—to test what it might look like in practice. The teams were open to it, but asked: what does that actually look like? I didn’t really know.

Then I realized, all my theories of social transformation have come from doing. Otherwise, it’s easy to get stuck in abstraction. How could I advocate for something I hadn’t lived?

Which is how I found myself on the ground in Matsu, filling 100+ vases with sand, listening to elders speak of waves and lilies. In my last missive, I shared what drew me to these islands and some context around the project. Nobody’s Pawn was born of frustration with Taiwan’s transitional justice processes, which insist on dividing the world into black-and-white binaries: victim vs perpetrator, Blue vs Green, China vs Taiwan. But Matsu reminds us that life is never so neat. So instead, we asked: What has shaped the spirit of Matsu? How might this spirit shape our forward becoming?

At the center of the installation is a giant 圍棋 (Go) board, its black and white stones once marking war and territorial control. In this former military stronghold, the board became a space for remembering together and imagining otherwise.

Participants inscribed their memories and aspirations onto chess pieces: one side holding Matsu’s spirit, the other a slogan for its future. On lands long inundated with slogans from above—”反共復國” (Fight Communism, Recover the Nation)—this was a chance to reclaim the form, defined by Matsu, for Matsu. Some that participants offered:

絕處逢生 越戰越勇 From hardship, life. From struggle, courage.

遠片海洋 包容一切 治癒所有 The vast ocean holds and heals all.

歷史的碎片 使島嶼更堅固 History’s fragments strengthen our islands.

Each chess piece then becomes a vase, filled with local flora. What others might dismiss as pawns reveal themselves as vessels of life. When the exhibition ends, residents will carry their vases back to homes and shops, each keeping a piece of Matsu’s story alive. Each vessel holding not only flowers, but the memory of who we are, and sparking conversations about who we might become.

At the gatherings, person after person told me they’d never had a chance to know their neighbours in this way. One grandmother said that even though everyone on these islands know each other, they rarely get to talk about the future they want. Yes, there are elections and referendums—on nuclear energy, on building casinos—but where, she asked, do we get to speak of who we are, what we yearn for?

The erasure of Matsuese voices is not unique. Around the world, communities are caught in the same games, their futures deemed expendable. Here in Taiwan, given the ever-present threat of invasion, news cycles fixate on Cross-Strait relations. But how do our struggles connect to those of Palestine, the Congo, West Papua? What ties can we trace between these frontlines of dispossession? What can they teach us about survival, and solidarity? The project was a space to wrestle with these questions.

Meeting Each Other

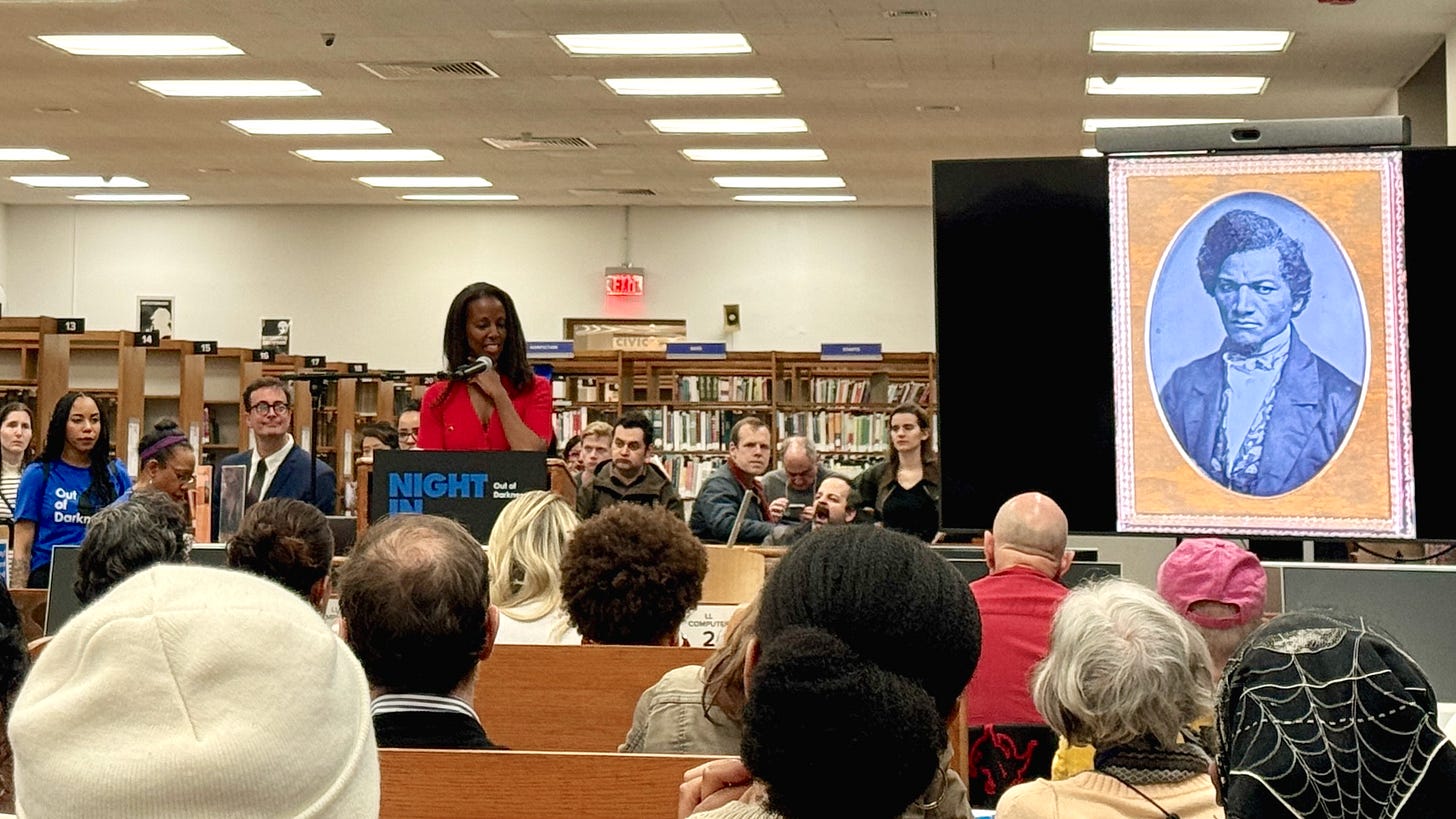

In March 2024, I attended Out of Darkness, an event at the Brooklyn Public Library meant to “confront our difficult era with honesty and curiosity.” People crammed between the stacks to hear Sarah Lewis speak on race and vision, and Fred Moten read Baldwin’s 1979 words on Palestine. The sessions were beautiful and raised vital questions, but they were only 15 minutes each, with no room for exchange.

After a stunning performance by Holland Andrews, I walked out to find nearly 800 people waiting to enter the 200-seat auditorium I’d just left. I asked someone what they were waiting for: Norm Finkelstein.

I felt frustration rise—we were missing the real encounter. With all respect, we could predict what Finkelstein was going to say; there were plenty of recent talks on YouTube. What we needed in that moment wasn’t another lecture—vital as his work has been—but to meet each other. If the night hadn’t been our going-away party, I might’ve grabbed flipcharts, organized the 600 people who weren’t getting in, then asked: What questions are you holding? Where does it hurt? What do you wish we could talk about?

What we needed was not more education, but more spaces for witnessing. For presence. For turning toward and tending to each other.

The longing for these spaces is what nudged me toward art as sandbox. As Amahra Spence reminded me, “artists give form to ideas”. Policy often gets stuck in abstraction—we speak of decolonization inside colonial institutions, of care within extractive systems. While the art world is certainly not immune, I admire artists’ drive to give form to what doesn’t yet have permission to exist, rather than endlessly trying to reform broken institutions. (Though we need more conversations about transition design…)

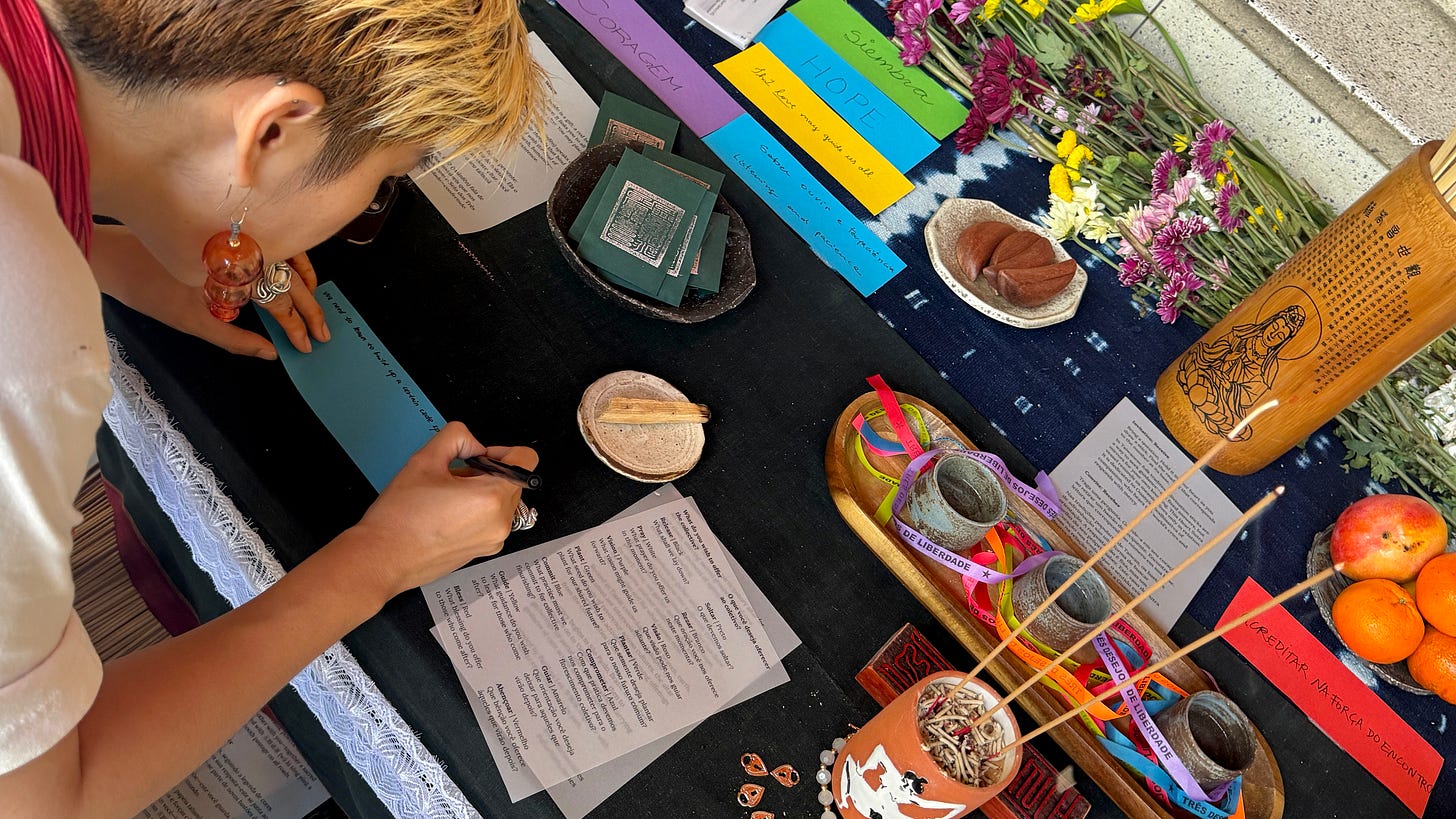

Enter An Altar for Our Ashes, a participatory altar offering new rituals for this moment of spiritual and ecological unraveling. The project grew out of deep disillusionment in my political work. Time and again, I saw how those “in charge” seem to have abandoned their humanity. In reparative justice processes I’ve supported, reparations are too often (mis)framed as charity. I want to shake them: this is not about your generosity, but your salvation. Releasing your stranglehold on the spoils of exploitation is not just about repair—it is about honouring those who still carry knowledge of how to live in harmony with land and with each other. Therein lies your salvation.

The altar launched at the iconic Casa do Povo with the inspiring SAVVY Contemporary—two dreams come true. The activation drew passersby into conversation about our spiritual practices and how we bring them into our politics. We shared what tormented our hearts, and how we were tending to them. The dignity of one another was assumed; there was nothing to “prove” to those far away who hold power over, but not care for, our survival.

I’m still processing the blessings from São Paulo, and the altar will soon travel to Laos. In the coming months, it will appear at sites of collective imagination—to remind us of our sacred ties—and at sites of reckoning (vigils, climate negotiations, political rallies) to bring sacred interruption. (I’ll share more soon.)

Beyond Gestures

The question remains: What would it mean to bring artistic imagination into policymaking and social infrastructure? Too often, artists asked to decorate political gatherings—perform a dance, show a work—where power-holders politely clap (“so moving!”) then return to business as usual. But what if we seriously studied their practices of witnessing, of tenderness, of care, of reimagining? What if we built real, tangible scaffolding around them?

People tell me I’m naïve: art should not be burdened with shaping policy or infrastructure; that is not ‘the point’ of art. I agree. And yet, if great art can drop us into another register, help us see each other in our full wonder, why wouldn’t we use it to reshape the world? Do we not have a responsibility to?

The art world loves to speak of gestures, and I get the instinct. But I long to hear more about mechanics and structures: not just what needs to change, but how to change it. If art is to offer blueprints for humanity, how do we ensure they move beyond gestures and into actions and mobilizations that shift the ground we stand on? (On this, the upcoming Global Artivism gathering in Salvador looks juicy.)

Otherwise, it risks collapsing into the same privileged abstraction of policy: flying to openings around the world, speaking of decolonization while neocolonial structures grind on. And if we’re serious about confronting ecological destruction—an understandably fashionable curatorial theme of late—we must also ask: What makes a global show worth the carbon of all that shipping and travel? What is offered in return that justifies the cost?

One glimpse comes from Vanuatu. In July, a Pacific-led coalition won a groundbreaking climate case at the International Court of Justice. This was possible because Ralph Regenvanu—an artist turned politician—had years earlier embraced 27 law students when most global diplomats dismissed them. He held a wider imagination: that their demand for global accountability was needed, was possible, and was worth fighting for. (I interviewed him and wrote about the campaign for The Nation.) This doesn’t mean artists must enter politics to make change, but it does show what becomes possible when artistic instincts shape political life. The entire campaign, rooted in Pacific narrative traditions, is a masterclass in how culture can fuel transformation.

In the São Paulo Bienal reader, co-curator Alya Sebti wrote that for art to be a force for change, it must circulate beyond exclusive circles: “Art must move; it must circulate and be shared. It must wander streets, enter homes, gather voices. Only then can it challenge dominant narratives, stir collective memory, and open pathways to new imaginaries.”

In discussing this point, Troels Steenholdt Heiredal asked whether it raises a harder question for cultural institutions: in this time, are memes having more impact than the kind of art privileged in galleries and museums? It reminded me of AX Mina’s Memes to Movements, which explores how memes have become vehicles of political imagination and mobilization, especially outside elite cultural spaces. In this way, they are evidence of the very circulation and new pathways Sebti calls for. What might the Western art world learn from this?

documenta 15, curated by ruangrupa, offered one of the most ambitious attempts to realize art as imagination infrastructure for the global majority. (If you’re curious, I wrote about their vision and practice for In These Times.) But the art press largely panned it. At the Socialism Conference in Chicago, an art writer sneered at the exhibit’s “NGO aesthetics”—an irony not lost on me, in a space dedicated to imagining alternatives to capitalism. Most documenta 15 artists were of the Global South, 95% without gallery representation, and without diasporic translators fluent in Western art discourse to render their work legible to its frameworks and poetics. This was not art as ornament or gesture. This was banners raised against the destruction of their communities. This was gathering to imagine new worlds beyond the machinery of plunder. This was global majority life, rendered as art.

Choosing Softness

“What’s softest in the world

rushes and runs

over what’s hardest in the world.

The immaterial

enters

the impenetrable.

So I know the good in not doing.

The wordless teaching,

the profit in not doing—

not many people understand it.”

Dao De Jing, Verse 43 (“Water and Stone”), Ursula K Le Guin translation

My deepening appreciation for how the soft (至柔) overcomes the hard (至堅) is what pulls me more and more towards art as a current of liberation. Water wears down rock. Wind shifts mountains of sand. Patience opens what pushing cannot. The Dao reminds us this is not metaphor, but physics and spirit: what is most gentle may be most transformative.

I struggled with Verse 43 for a long time, as it challenges the activist mind. Especially in crises, we’re taught to push harder, shout louder, be more unwavering. And yet, poetic restraint and silence are what work most profoundly on me.

While I was trained to prove with facts and data, I also know they can be twisted to serve almost any argument—and people pull away when they feel they are being persuaded rather than honestly heard. Perhaps what we need instead is support to return to our primal knowing: that we belong to each other.

I think of Julianknxx. In fall 2023, I was in London for Rehearsing Freedoms. After a particularly intense session on power, the wise Nkem Ndefo told me to go home and rest. Instead (the one time I didn’t heed Nkem), I returned to his show at the Barbican. I’d seen it once already, but it gave me solace: to bask in what endures, and to witness the many gorgeous manifestations of Spirit.

Later, as part of a reparative justice effort, I’d hoped to weave Julian’s work in. By the time the organization was ready, the show had closed. Instead, we grounded an exercise with “Castaway” by aja monet and hosted Sanah Ahsan, two brilliant poets whose offerings greatly enriched the process. Still, I wonder how different the conversations might have been if we’d held them inside the container of the show, enveloped by song and movement, mesmerized by voices and bodies that you couldn’t—and didn’t want to—turn away from.

What different decisions might we make when we are enraptured and spellbound by one another?

This question returned to me again and again in Matsu and São Paulo, as I savoured offerings by spirit workers like Adama Delphine Fawundu, 彭雅倫 (Ellen Peng), Juliana Dos Santos, 劉梅玉 (Liu Mei-Yu), Maria Magdalena Campos Pons, and Rajyashri Goody. These artists remind me of Verse 43’s truths: what seems soft is often what endures. What’s invisible—tender love, soft presence, steadfast witnessing—shapes more than brute power.

Let us fight less and feel more.

Let us be soft when the world is so hard.

May a revolution of tenderness carry us back to each other—

and teach us how to mend all that has shattered.

***

If you made it this far (!!), thank you. I appreciate you spending your precious time with me. A few notes:

Deep gratitude to friends and fellow travelers whose conversations and work informed this thinking, among them Adama Delphine Fawundu, Amahra Spence, Babajide Adeniyi-Jones, Berette Macaulay, Camille Sapara Barton, Claire Mellier, Danielle Olsen, Ethel Tawe, Farzana Khan, Gabriella Gomez-Mont, 葉浩 (Yeh Hao), Julian Aguon, Julian Knox, The Laundromat Project fam, Naomi Beckwith, Ralph Regenvanu, Rajyashri Goody, Rory Tsapayi, ruangrupa friends, SAVVY Contemporary crew especially Mokia Dinnyuy Manjoh, Sanah Ahsan, 上官良治 (Shang Kuan Liang-Chih), Teesa Bahana, Tobechukwu Onwukeme, Troels Steenholdt Heiredal, and Vishal Prasad.

On forward dreaming: When I first spoke with SAVVY about São Paulo, I’d hoped to link their efforts to climate justice initiatives, including the Global Citizens’ Assembly, around COP30. That isn’t happening for many good reasons, but the dream is still there. If you’re working in these spaces and want to explore intersections, I’d love to be in touch.

On a paid newsletter: I’ve decided to turn on payments here because, well, I’m trying to figure out how to make a living that’s true to my values. I’m so very grateful to those who’ve already pledged support and encouraged me to do so; it means the world. This work will always remain free. But if you have the means, and if these reflections have offered you something and you’d like to help sustain the labour behind them, I’d deeply appreciate it.

Beautiful, thanks for sharing these reflections.

So much food for thought here 💖 My thoughts turn to how those working with and around artists need to be in order to centre their vision without asking them to become administrators and managers. What might that scaffolding look like?

And 'we need to have more conversations about transition design' - 1000% this!