on seeing and moving together

reflections from Laos: on the long tail of war and on how we heal amid ongoing horrors

I pause in front of a wood shed held up by rusted four-foot bomb casings and turn to my guide, eyebrows raised. “It’s sturdy,” he shrugs. “People use what they can.”

We’re in Xieng Khouang, a highland province in northeastern Laos. During the American War in Vietnam, this became one of the most heavily bombed places on earth. To this day, Laos remains the world’s most bombed country per capita.

From 1965 to 1973, the United States conducted more than 580,000 bombing missions here, dropping over 270 million cluster munitions, more tonnage than all U.S. bombs dropped on Germany and Japan in World War II. Around 80 million of these bombs never detonated, and no one knows how many still lie buried. A quarter of Lao villages remain contaminated, including 41 of the country’s 47 poorest districts. Since the war ended, unexploded ordnance (UXO) has killed or maimed more than 20,000 people.

Every day, small teams from local and international nonprofits clear the land meter by painstaking meter. Yet progress remains slow: as of 2012, only 0.28 percent of contaminated areas have been declared safe. As climate change accelerates erosion, floods, and landslides, long-buried bombs are resurfacing, making even cleared grounds dangerous again. It is a Sisyphean task.

Poverty compounds the danger. Some villagers have tried to pry open and defuse bombs themselves so they can sell the scrap metal, perhaps US$40 for a large casing. Others repurpose them for daily use, as cookware, house stilts, or garden equipment. In a landscape scarred by conflict and neglect, people make do with what remains.

As historian Alfred McCoy reminds us, Laos wasn’t a sideshow to Vietnam, it was U.S. empire’s laboratory of modern war. Here, America rained down its new inventions: computer-guided bombing, cluster munitions, gunships, and early drones. In this small country, then one of the world’s poorest, the world’s most powerful nation engineered a new kind of violence: distant, unaccountable, shameless. These methods and technologies have since continued to devastate lives from Iraq to Bosnia, Afghanistan to Libya, Syria to Palestine.

I’ve come to Xieng Khouang to try and understand what it means to live in the long tail of war. The world rallies, as we should, against moments of spectacular, kinetic violence, but what of the quiet, punishing aftermaths? How do societies endure amid the remnants of war? What does life look like when the land itself remains deadly, when daily tasks carry lethal risk? What does accountability mean when survival depends on the very powers that caused the harm? In such places, what does healing even mean?

In one village, we meet a 90-year-old woman who had been a local Pathet Lao leader. At nine, she was sent to Hanoi to study under the Vietnamese Communists; when the war began, she returned to fight. While stationed in Xam Neua, she tells me, beaming, she killed four Americans. She repeats this five times in the hour we spend together, eyes shining. Although she is revered here, a hero to her people, her government pension rarely comes. For years she has petitioned the state for what she is owed, to no avail. The comrades who once sent her to war have no use for her now.

Perhaps her insistence—her claiming of agency, her retelling of the glory days in a history that has forgotten her—is, too, a form of healing.

At Tham Piew Cave, a U.S. rocket attack killed 374 people on November 24, 1968. For eight years, local families had been living in the cave to escape the relentless bombing. When the rocket struck, their shelter became their grave.

Six decades later, the roof is still blackened. I stand in the stillness and try to imagine the single instant in which so many lives were turned to ash. The tears come.

“Fucking Americans,” my guide B mutters, the only time in our three days his composure breaks.

We gather some stones and stack them into a small cairn. “It is how we honour the dead,” he explains. Later, a local friend tells me that’s something only tourists do.

But perhaps this doing-together with outsiders—a fumbling of hands that don’t know where to place their sorrow, a brief stilling of the unanswerable—is, too, a gesture toward wholeness.

In Muang Khoun, the former capital of Xieng Khouang, we visit Wat Phia Wat temple. The ancient city was almost completely flattened by bombs, leaving its Buddha blackened and cracked. Instead of repairing or replacing it, the community built a new temple beside it. People travel from far and wide to this scarred Buddha; he is said to be particularly skilled at curing illness.

B tells me this is government policy: to let these ruins stand, so people remember what was destroyed. Outside the district office sits the shell of a bombed hospital. Schoolchildren come to these sites to learn what was done to their country, and how their people endured.

Perhaps these acts—to keep the wounds visible, to let what survived stand as witness and as teacher—are, too, a form of prayer for what remains.

After a long day on the road, B mentions a Hmong man who’s been making something remarkable, and we pull off the highway to find him. He is 65 and has spent years building an open-air museum of Hmong culture. During the war, many Hmong fought for the CIA-backed Royal Lao Army; when the U.S. withdrew in 1975, they were left to face the consequences.

Villages emptied. Families fled across the Mekong into Thai refugee camps, and later to countries like America and France. Those who stayed were often branded traitors, sent to re-education camps, or marginalized in public life.

What this elder is doing—reassembling what has been scattered, giving form to what has survived—is, too, a way of mending what history broke.

The whole trip, though we were in areas declared safe, I still felt a flicker of fear each time I stepped off the road, especially in the rice fields. It was harvest season: people waded through the gold, cutting stalks, laughing, helping their neighbours. Still, I couldn’t shake what I’d heard: in Xieng Khouang, some 80 percent of residents still farm land they know or fear may hide live explosives.

But poverty leaves little choice. For families who depend on every meter of soil to eat, danger is a companion they’re forced to endure. They farm carefully, aware of the risk, because not doing so would simply mean a slower death.

i am willing to shelter and hold your pain

I was in Laos to help host a gathering of feminist artists and cultural organizers from across Asia working at the intersection of art, justice, and human rights. Convened by Urgent Action Fund and Mekong Cultural Hub, two organizations I deeply respect, our time together was anchored in these questions: In a world of structural violence and so few safety structures, how do we support each other? How do we hold one another in a world that keeps breaking us open? How do we weave ecosystems of care that can nourish and sustain us?

Given that participants came from 15 countries, we began by asking what we even meant by care. Across our cultures, we discovered, care is rooted less in sentiment than in action: presence, deep attention, listening, tending, sharing another’s burden. In Bangla, যত্ন (yatna) means to nurture, to be mindful, to protect, to love, to gather inner strength. In Khmer, ថែទាំ (thetam) means to tend to someone with love and responsibility and យកចិត្តទុកដាក់ (yokchett toukdeak) means to place your heart in something. In Vietnamese, mình thương bạn (I care for you) signals I am willing to shelter and hold your pain.

Care across Asia, I was reminded, is not a feeling but a practice. It comes alive in countless, daily acts of service: asking if a beloved has eaten, cooking for each other, holding space, finding ways to share the weight of what others carry.

Our conversations were closed-door, so I won’t repeat details here. But I emerged deeply moved by what my sisters are building, often in impossible circumstances. So many of the freedoms I take for granted—naming those who cause harm, tracing the roots of injustice, even gathering in a room together—are perilous for those who live under constant surveillance and political threat.

Witnessing the courage of those who keep creating and fighting for their communities reminded me how sacred these freedoms are—and how fragile. Solidarity, I was reminded, is care in motion: standing with those whose voices are constrained, using our safety to make visible their struggles, sharing risk, and tending to each other in a world that gaslights and silences us.

In Laos, that gaslighting is almost institutionalized, woven into the very structures of aid and “development”. The Mines Advisory Group, one of the key organizations clearing UXOs, runs visitor centers in both Vientiane and Phonsavan. At each, a wall displays the logos of its funders: the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, UK International Development, a few small nonprofits—and the American flag. Not a U.S. government seal, but the flag itself, bright and proud.

I asked a staff member why. They shrugged: the U.S. State Department is their biggest donor, and they’d requested it that way.

These contradictions hung heavy in our conversations that week. From Myanmar to West Papua, China to Vietnam, artists asked the same question: how do we care for one another when the structures around us are designed to harm and divide us?

The answer we kept coming back to: we create our own spaces.

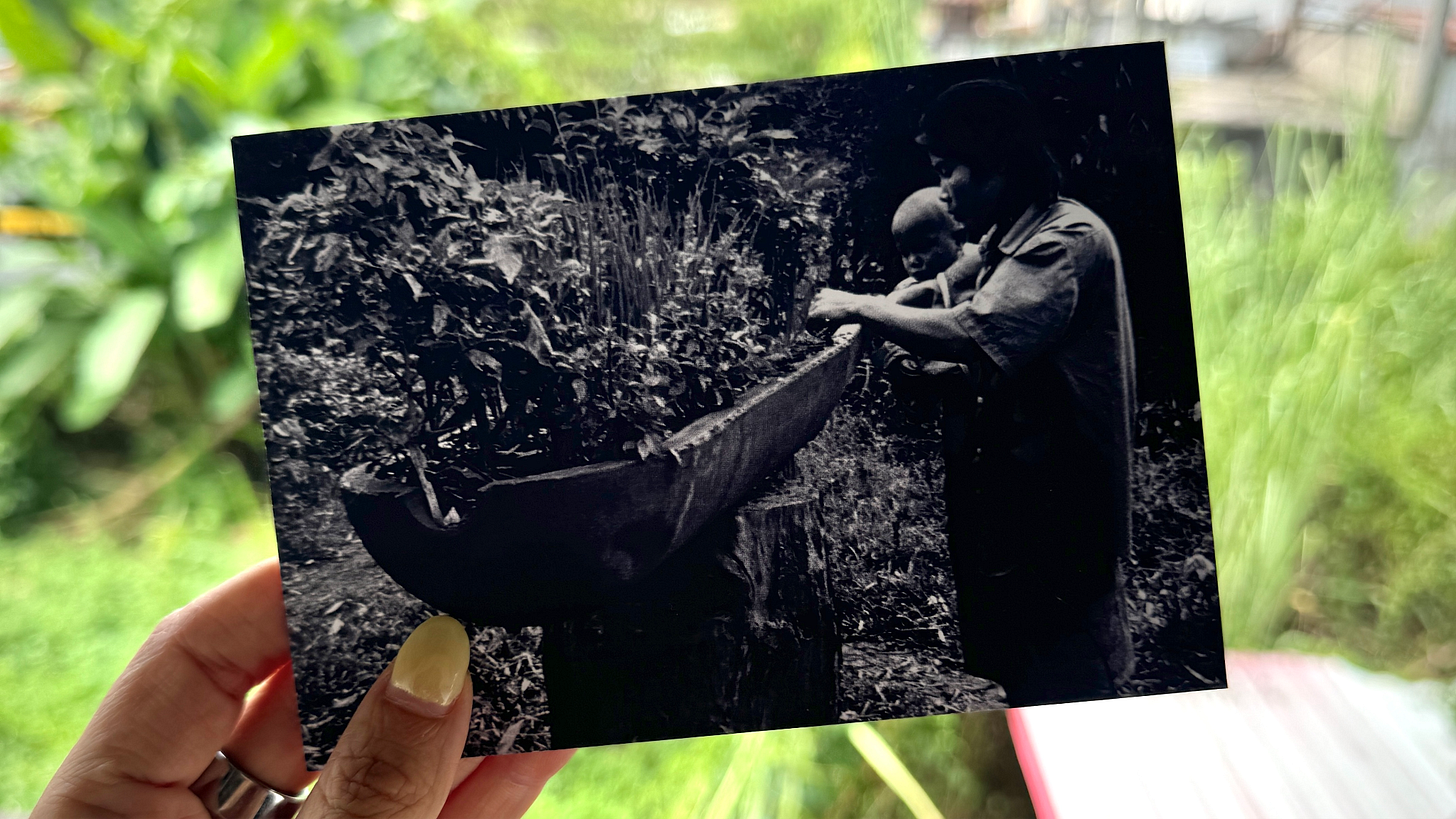

This gathering marked the second activation of An Altar for Our Ashes, a collective ritual I’ve been carrying across geographies. In Laos, people were invited to bring objects that embodied care. Among the offerings: a massage tool, hand-harvested tea, a shamanic talisman, a woven ring, hand-stitched art, and postcards artists had made in their communities. Each offering joined the altar’s growing constellation, left for future kin who might gather here.

Over the week, we held rituals that were gentle, grounding, and sometimes tearful. We made wishes for liberation, prayed, shared stories and secrets, and did somatic practices to release what no longer serves us. Again and again, I was reminded how much we need these spaces—how, even and especially in lands marked by violence, people find ways to offer each other tenderness and care.

After one ritual in Xieng Khouang, a Burmese artist asked me, how do we heal? Given everything that has come before, and the horrors still unfolding, what does healing even mean?

Since the 2021 military coup, artists and journalists in Myanmar have faced imprisonment, torture, and even exile for the smallest acts of dissent. As we watched her film, I realized her art was already answering the question. In it, she examines the Burmese people’s fear of the military: where it comes from, how it lives in the body, how it shapes silence.

In a country where such questions are dangerous to ask aloud, her practice opens space to speak the unspeakable. To look directly at fear is the first act of breaking it. This, too, is healing.

Late-stage capitalism would have us believe healing is something we buy: therapy sessions, wellness retreats, self-care products. But true healing has always been collective. It is singing and dancing together, eating duck blood salad together, drinking too much rice wine together, making an afterparty with Beerlao and roti in the park together.

Healing is holding a friend’s grief without trying to fix it. It is making art together so that what is unbearable can find form and, in doing so, begin to move. It is speaking aloud what our communities deserve, and cheering each other on as we dare to build it.

Healing, as bell hooks reminds us, are acts of communion.

The altar also opened conversations about the role of religion in how we confront structural harm. We were in Laos, where two-thirds of people are Buddhist, and many of us come from societies where Buddhism shapes moral and political life. We explored how certain concepts—like karma or detachment—are sometimes twisted to explain away suffering, asking people to accept what is unacceptable. When injustice is read as fate, it numbs our will to resist.

We discussed the teachings of B. R. Ambedkar, whom I was introduced to a few years back, and was stunned I hadn’t known sooner. A fierce anti-caste activist and principal architect of India’s post-colonial constitution, Ambedkar reimagined Buddhism not as spiritual retreat but as a revolutionary path toward social liberation. Rejecting the Hindu caste order, he envisioned a Buddhism grounded in human dignity and equality.

Studying his work has made me wonder why Thích Nhất Hạnh, and not Ambedkar, has become so globally embraced as the model of socially engaged Buddhism. Could it be that while Hạnh’s teachings are beautiful and true—and deeply radical in their own way—they are also more palatable to those in power? Ambedkar, on the other hand, calls us to confront power head-on, so we transform rather than transcend it. This is profoundly uncomfortable to those who seek peace without reckoning.

(I’m deeply grateful to Arjun Kapoor of the Centre for Mental Health Law and Policy for introducing me to Ambedkarite thought, and to Rajyashri Goody of Metta Pracutti and Gauri Nepali of Just Futures for our conversations that continue to deepen this thread for me.)

the art of moving as one

Our gathering then flowed into Meeting Point, an extraordinary convening of artists and cultural organizers from across Asia, hosted by Mekong Cultural Hub. I was deeply inspired by Jaya Iyer, who uses Theatre of the Oppressed to foster empathy in communities fractured by violence; Andrei Venal of DAKILA, the Filipino collective reimagining education through cultural organizing; Thị Bùi Anh and Lê Dinh Hoang Quyen, reviving the nearly lost art of bamboo boat-making in central Vietnam; artists from West Papua creating songbooks to safeguard Indigenous musical traditions from erasure; and artists from Laos using forum theatre to help communities confront ecological devastation along the Mekong.

The energy was electric, alive with the tender revolutions we were each stewarding, and the sense of deep kinship with those also dreaming and building the future into being.

At Khao Niew Theater, three puppeteers moved a single puppet with such tenderness I cried. To animate its gestures, they must study how beings move: how a child plays, how an elephant startles, how curiosity travels in the body. Such work demands love: the kind born of deep attention, of letting the lives we study move us in return. The intimacy required of these artists—to bring coconut shells to life, to breathe as one body—was a profound lesson in attunement.

So much of contemporary art insists that creation happens in isolation, that artists must excavate some deep inner genius. But the puppeteers reminded me of the deeper truth: the greatest art is born in relation, through seeing each other, through moving together. Art, like healing, is collective movement. And that was what I saw everywhere at Meeting Point.

***

On my last day in Laos, I took a cooking class. There was a young Austrian couple in my group, on a few weeks’ holiday in Southeast Asia. They tell me they started in Singapore—which was aaaamazing!—and now regret coming to Laos. There’s nothing to see here, they shrug.

Rage surges within me. I think of all the beauty, the care, the love, the warmth I’ve experienced these past weeks, and how easily they dismiss it all. My body tenses, the instinct to fight kicking in. I brace myself to lecture them about the bullshit of “development”, about Western extraction, about the privilege of not seeing. Then I pause. I take a breath. And I realize what I mostly feel is pity—it’s not just that they don’t see, it’s that they cannot.

I turn back to my mortar and pestle and keep seasoning my mok pa.

It was delicious.

I have no Dao De Jing verse to offer this month. As the text begins:

The Dao that can be spoken is not the eternal Dao

The name that can be named is not the eternal name(Verse 1, Dao De Jing, Derek Lin translation)

Like care, the Dao can’t be grasped through intellect, it must be lived and felt. (As someone who often lives in my head, this has been a tough lesson, one I keep relearning daily.) Study can guide our practice, but nothing replaces the experience of moving with it.

Words, Laozi reminds us, can only offer fleeting glimpses. He was wary of language: naming can be dangerous, because once we name a thing, we start to defend it, to divide around it.

So this month, I’ve simply been living with the Dao, attuning to its flow in countless small, tender, precious moments.

Thank you for being here, for reading, and for attuning with me.