Holding Brave, Tender Space in Times of War

On geschichtsmüdigkeit and multidirectional memory, refusing the weaponization of complexity, and creating spaces to hold each other’s tender humanity and pain

I just got back to New York after nearly a month away. What a month to be away from home—from my beloveds, the people I feel safest mourning and processing with, and from the spaces and rituals that ground me.

In this period, I spent time in new spaces, grappling with the horrors of what is unfolding in Palestine and Israel. It was eye-opening to experience how different communities—from academia, the arts, government, and activism, albeit all in major Western cities—responded, and to reflect on what such disparate responses might mean for our fights for social transformation. What follows is a messy attempt to process what I learned.

This post contains no hot takes. There are too many of those right now, especially from armchair historians and political scientists in the West. I have no place adding to the pile. Neither is this trying to document what is happening; there are other spaces for that. It is, however, an attempt to grapple with the broader challenges this crisis has illuminated: around our ability to grapple with complex histories, to have hard conversations, to challenge corrupt power, and to understand and struggle together—courageously and imperfectly—toward justice. I don’t pretend to have any answers, but as a facilitator and mediator working across political, cultural, and geographic divides, these are the questions that consume me.

I’ve tried to organize my thoughts into three parts: i) observations on how different communities are responding (or not) to the Palestinian struggle for liberation, from my last few weeks; ii) reflections on broader dynamics we’re witnessing and the implications for our movements, and iii) some meandering closing thoughts.

Part 1: Observations from Berlin, Toronto, London

Berlin: The Violence of History Weariness

I flew to Berlin on October 8. I felt tense boarding that plane—the Hamas attack had just happened, everyone was reeling, my feeds were a mishmash of grief and Fanon. We did not know what was coming, but we knew it would be bad. I consoled myself with the fact that I was traveling to a conference on transnational solidarity; if I couldn’t be with my humans, then surely activist-scholars would be a nice consolation. Together, I imagined, we could examine unfolding events and discuss what it meant to move in solidarity.

The conference was a shock. The speakers were largely German philosophers, sociologists, and political scientists. Other than Wendy Brown, who briefly acknowledged the crisis at the start of her talk, no one else even mentioned what was happening in Palestine and Israel. The silence was deafening.

By the time I got up to speak, on Oct 11, I felt like I was going mad. What was this conspiracy of censorship? Was anyone else feeling suffocated? I prefaced my talk with a diplomatic but pointed call in: What is the point of theorizing about solidarity if our theories are not tested against concrete struggles? Why bother with drafting principles and declarations if they are not rooted in real conflicts and movements against oppression?

Berlin has the largest Palestinian diaspora in Europe, yet the government has banned the Palestinian flag, the keffiyeh, the chant “from the river to the sea”, and Palestinian solidarity events. Police have been using pepper spray, water cannons, and brutality to shut down protests. What did the German scholars who had built their careers by theorizing about solidarity have to say about these developments? Wasn’t a gathering of activist-scholars—and absent politicians and media—the exact place to be grappling with these questions?

After my talk, several of the organizers thanked me for my comments, but no one picked up the thread. Fear of saying something divisive had led to total avoidance; to saying nothing. I was dumbfounded.

To try and make it make sense, I headed to Berlin’s Topography of Terror. There was something I needed to understand about German Erinnerungskultur (Culture of Remembrance), but I wasn’t sure what. The museum details how the Third Reich terrorized and persecuted Jews and other oppressed peoples during World War II. There, in front of displays of unspeakable tragedies, I tried to put myself in the shoes of Jews during the Holocaust—and of Germans who later grappled with their fatal complicity. I tried to understand how Jewish anguish and German shame live on, and what the October 7 attacks (and its “Holocaustization”) must have triggered.

I was lucky enough to spend an afternoon with the incredible SAVVY Contemporary team. There, curator Mokia Laisin introduced me to the German word geschichtsmüdigkeit, or history weariness. The term is used to describe a sense of exhaustion or fatigue with the study or recounting of history, often in the context of public discourse or societal attitudes towards historical narratives.

I can understand that Germans are weary of being the bad guys in World War II. But Germany’s attempts to make amends for the Holocaust has led to its unshakeable solidarity with the state of Israel, its Staatsraison—even as the latter commits the same types of atrocities for which Germany is atoning. German guilt has led to some trying to rewrite history, to say that anti-Semitism was imported by Muslims. German guilt means that Palestinians now pay the price for its past mistakes and present-day cowardice. As peace and conflict scholar Sa’ed Atshan observes, “While many [Germans] think that they’ve moved past the ultranationalism, violence, and racism of the Nazi regime, they’ve now put themselves in a position in which they are reproducing those patterns with regards to the Israeli state.”

Toronto: Truth & Reconciliation as a Worldmaking Project

From there, I went on to Toronto, where I was honoured to cohost a gathering of 7 Generation Cities, a new collaborative of Indigenous and municipal leaders designing cities rooted in care, radical inclusivity, and regenerative ecologies. The name draws from the Seventh Generation Principle of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and similar teachings that ask us to learn from the wisdom of our ancestors and of the Earth, and to take decisions that serve future generations.

What a change from Berlin. This community—which has been stewarded by three brilliant leaders Tanya Chung-Tiam-Fook, Jayne Engle, and Pamela Glode-Desrochers—grappled with questions like is it possible to build decolonial spaces while working with and through colonial institutions? What are concrete opportunities and ways to return land—quickly and at scale—to Indigenous stewardship? (This is a question both of justice and of planetary flourishing. Although Indigenous peoples comprise less than 5% of the world population, they protect 80% of the Earth’s biodiversity.) How to embed truth and reconciliation in how we build and steward social infrastructure?

These are urgent, vital questions. While the gathering was centered on initiatives in Canada, we acknowledged the ongoing horrors in Palestine and Israel, and of the breaking news that Australia had voted to reject constitutional recognition of its Indigenous communities. Against these backdrops, we grappled with what repair is even possible as colonial violence continues—and how to look not just backward but forward in how we understand reparations. As Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò reminds us, a constructive view of reparations is “less about the transfer of resources… as it is about the transformation of all social relations… re-envisioning and reconstructing a world-system.” Reparations is ultimately a project of worldmaking.

I thought about what forward-looking reparations mean in this moment, as we lob explainer after explainer online, trying to one-up each other on who has the best analysis, whose histories (and thus claims) go furthest back, whose pain is more legitimate, whose humanity matters more. We spend so much energy litigating these points—and history is important, but there will always be multiple positions and lenses through which to understand it—and not enough time asking: What kind of humans do we want to be? What is the quality of the world we want to live in? Quality in terms of how we conceive of I, you, we, and us. In terms of how we meet and care for each other. In terms of how we hold our intersecting histories of pain and of hope as we forge a forward path.

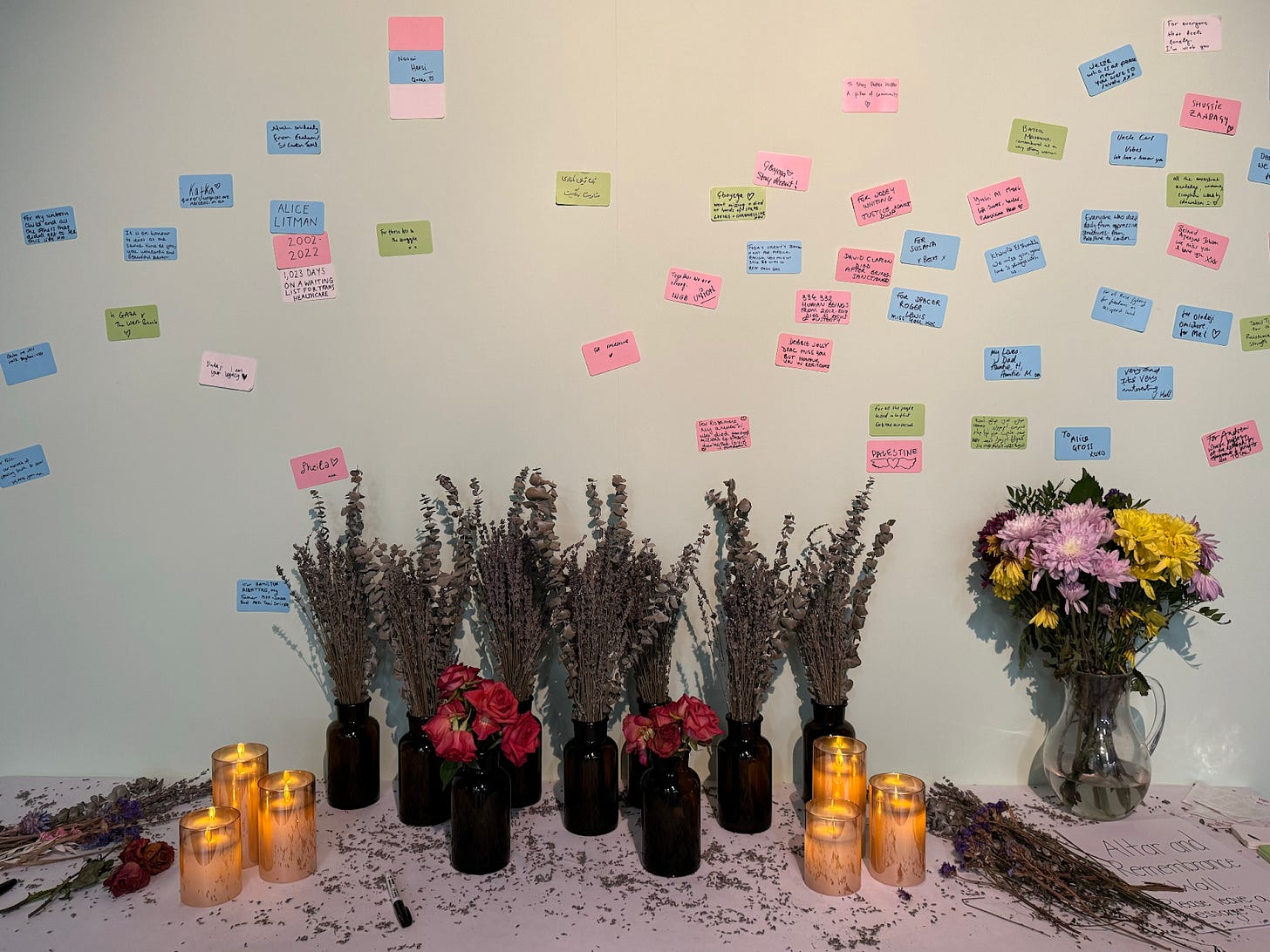

London: Creating & Holding Brave Space

Then it was off to London—yes, I recognize it was a terrible itinerary; no, I had not planned it that way—for Healing Justice London’s Rehearsing Freedoms festival. My beloved Farzana Khan is one of the great visionaries of our time, and HJL, which she co-founded and co-directs, is doing groundbreaking work on community health and structural justice.

The festival title is inspired by Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s assertion that we must “rehearse the social order coming into being”. Led by and centering communities who have been historically oppressed—people of colour, people living in poverty, queer people, disabled people—it is a festival for us to come together, share knowledge and practice, love on and resource each other, and build the infrastructure we need for our healing and liberation. Events (all still upcoming) include politicized Tai Chi workshops, collective rest sessions, elders’ circles, community dinners, and a People’s Health Assembly.

The day I landed, I was on the tube on my way to my panel (on narrative organizing for social movements) when Farzana called me. Given that Gaza’s Al-Ahli Arab Hospital had just been bombed, they wanted to pivot the session to focus on narratives around Palestine and Israel, and what cultural organizing might look like in this time. Would I be willing to chair the session instead? I hesitated: Given my positionalities, I was far from the ideal host; yet given we were two hours out, someone needed to step in. So yes. I was craving a space to process in community, and HJL was generously offering one.

And so we came together. To mourn, to wrestle, to rage, and to begin to strategize. Some of the questions we grappled with: How do we remain vigilant against attempts to dehumanize? How do we reject the weaponization of complexity? In terms of narrative organizing, how should we move when establishment media is so captured, misinformation is flying, and we’re facing structural gaslighting every day?

I explore these questions in the next section. But for now, what I want to uplift is how HJL responded in the face of unfathomable tragedy. They knew we needed space to cry, to yell, and to hold each other; they knew that in doing so, we retain our humanity which dominant culture works so hard to erode. So while they had spent months perfecting the festival program, they immediately reengineered it to respond to what the world was craving. One night, when my tank was nearly empty, sisterwoman vegan placed a heaping plate of Caribbean soul food in front of me. It nourished me physically and spiritually. With my belly full, I headed to the dancefloor where my dear Camille Sapara Barton led us in a tender centering practice to open their DJ set. Given everything that had been happening, I had thought I wouldn’t last past 10am, but I stayed until the very last beat at 2am. For hours, I danced to move the grief through my body, so that I didn’t stay stuck and saturated. It was the medicine I hadn’t realized I needed.

Importantly, HJL also created support spaces, both for Palestinians and other communities. I had the privilege of both attending and volunteering at these spaces. Two support sessions held by Nkem Ndefo, a pioneer in politicized somatics, were particularly transformative. In one, she guided me through my first therapeutic tremor. In another, I realized I had gone numb and could no longer take in what my fellow participants were saying. Nkem asked me to chug down some water to stimulate my vagus nerve, then to go for a brisk walk. Within minutes, I had moved the feeling back into my soma—profound fury at our so-called leaders, deep despair at my own impotence—and sat sobbing with an Iraqi sister. By feeling and processing my emotions, rather than denying them because they were too painful, I cleared the space I needed to continue listening and strategizing.

The entire Rehearsing Freedoms festival is a celebration of our humanity, our creativity, and our ability to dream and craft a new world. It is a balm for our spirits. There are two more days of programming (across London and online), and select past sessions are here.

Part 2: Reflections on What We Must Learn

The last month has brought up many questions for me. I’ve wondered what to do with them. It feels like neither the time nor (given my positionality) my place to raise them—my energy is better spent supporting loved ones with connections to the region; learning and practicing courageous conversations; and putting my dollars, body, and attention where affected communities are directing us.

Yet, as a cultural strategist and facilitator, I can’t stop thinking about these questions. For while the crisis in Palestine and Israel is among the most high profile and explosive of my generation, there are and will continue to be countless issues where traumatized people are in conflict, where imperialist interests prop up injustice, where media fuels polarization and disinformation, and where innocent people continue to pay the price.

And so I offer my reflections here, in the hopes that doing so might help me connect with others wondering the same. Others holding the type of conversations I seek. Others yearning for / building new platforms that are independent and that nourish our interdependence. If that is you, I’d love to be in touch.

On refusing the weaponization of complexity

Since October 7, we have heard “this is complex” over and over as a way of disempowering people, making us feel like we don’t know enough / will never know enough to engage. This tactic, of course, is not unique to this situation—I’ve seen it plenty in other spaces, where those with fancy pedigrees, armies of lawyers and economists, and vocabularies stuffed with 10-dollar-words weaponize complexity to confuse a situation and undermine righteous rage.

Similarly, I’ve heard people use “this is complex” as a way to avoid talking about the crisis, especially those who are not Jewish, Muslim, or Arab; it is used to justify their own shrug-and-look-aways. But as Ta-nehisi Coates recently put it, “The most shocking thing about my time [in Occupied Palestine] was how uncomplicated it actually is. I’m not saying the details are not complicated. But you don’t need a PhD in Middle Eastern Studies to understand the basic morality.”

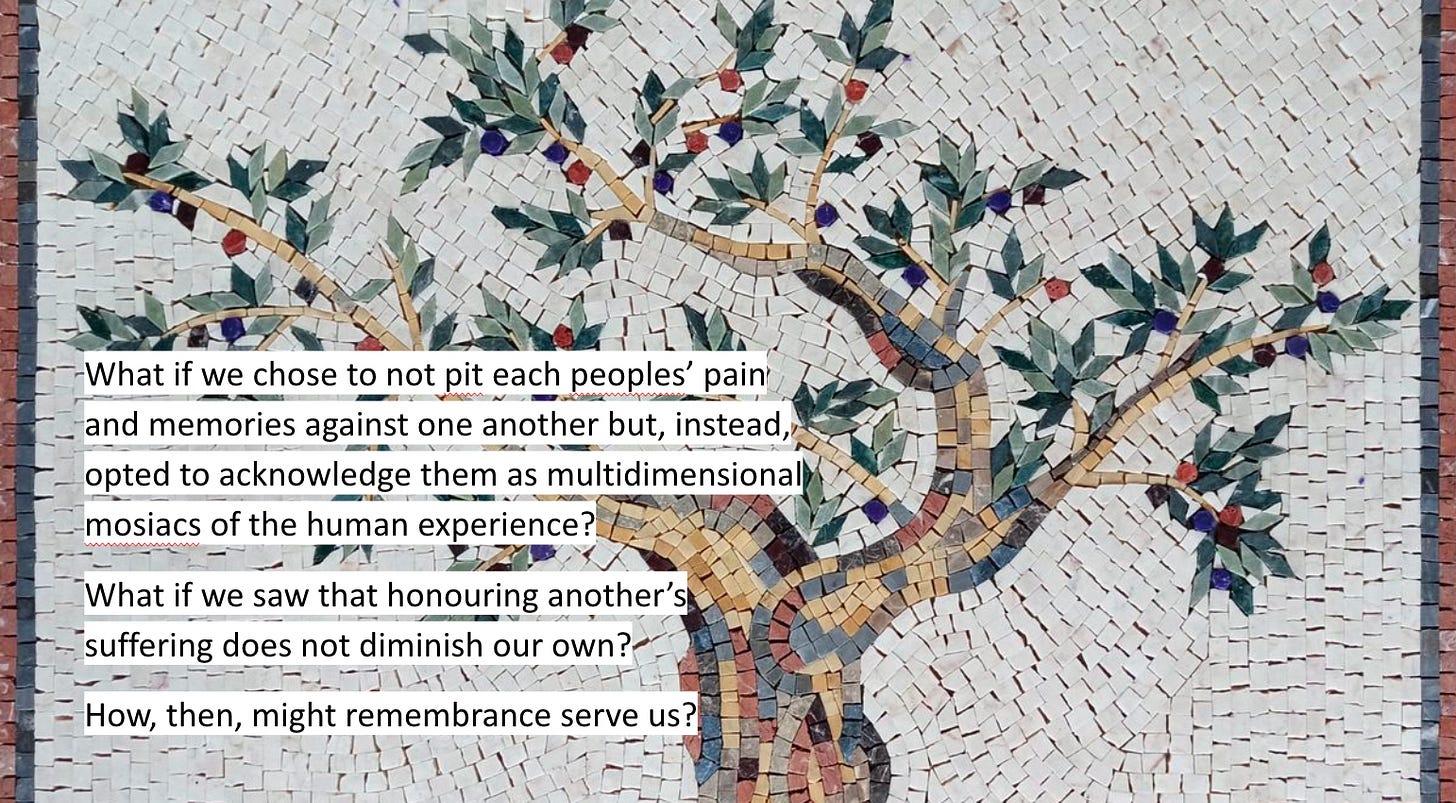

So how do we grapple with complexity? Here, I find Michael Rothberg’s concept of “multidirectional memory”—a way to examine what happens when histories of extreme violence confront each other in the public sphere—quite helpful. “Remembrance is intrinsically a productive, multidirectional process of bringing different histories and actualities into relation,” says Rothberg. “As a constellation of past and present and of here and there, memory necessarily possesses a ‘comparative’ or relational dimension.”

There is no one truth; there are only different perspectives and lenses. What if we chose to not pit them against one another but, instead, opted to acknowledge them as multidimensional tapestries of human experience? What if we saw that honouring another’s anguish does not diminish our own? That recognizing our responsibility and complicity in another’s pain—through our lineage, our dollars, our (in)actions—need not be an indictment on us, but rather a call to stop the suffering? How, then, might remembrance serve us?

In The Implicated Subject, Rothberg shows how conversations about Israel and Palestine always unfold against the backdrop of powerful memories of death and dispossession—namely memories of the Holocaust, the Nakba, and the ongoing occupation. In these contexts, the memories at stake are often contested. He warns, however, against the antagonistic logic of competition and hierarchy—or, in 2023 parlance, the Oppression Olympics. The logic is dangerous and futile. and has led to a situation where when Palestinians ask for rights, some Israelis feel threatened. The lie of perpetual victimhood distorts thinking, so that a chant for liberation (“from the river to the sea”) is interpreted as a threat of annihilation.

Rothberg, a Jewish scholar of the Holocaust, advocates for decentering the Holocaust in global memory studies. For its centrality and continual invocation “keeps in place Israel’s most potent legitimating symbol: a narrative genealogy of ultimate victimization coupled with absolute innocence.” It also diminishes oppression and suffering against other populations which, as we see today, has deadly consequences.

As Natasha Roth wrote in +972 : “Indeed, if the legacy of the Holocaust is interpreted to present Israel with carte blanche to cage, bomb, starve, dehydrate, and otherwise exert necropolitical power over the 2.3 million Palestinians in Gaza—almost half of them children—then ‘never again’ does not merely ring hollow. It becomes a call for unchecked violence, a war cry in an eliminationist campaign of retaliation.”

Rothberg’s argument resonates with me, and with other friends of the global majority who grew up in the West. We are members of different diasporas but all grew up studying the Holocaust, often before learning about our own histories. I remember in Grade 5, I devoured books like The Diary of Anne Frank, Number the Stars, and The Devil's Arithmetic. They haunted me, and I became obsessed with this unthinkable tragedy. I wrote book reports and gave class presentations on the Holocaust’s horrors. I was taught, and fervently believed, that it was the greatest stain in human history.

It was only in my early 20s that I learned of the 228 massacre, which has sometimes been described as Taiwan’s Holocaust. (I dislike this framing.) It was only in my late 20s, as I worked across the Global South, that I understood the depth and cruelty of structural violence inflicted on the global majority in order to maintain capitalism in its current form. And it was only in my 30s that I truly began to grapple with the genocide of Indigenous populations, on whose stolen lands I was now a settler, and what truth and reconciliation on Turtle Island might mean. Friends have expressed the same: For so long, many of us have known much more about Jewish pain and oppression than our own, as our ancestral histories were erased from Western textbooks.

A Haitian friend admitted that because of this dynamic, they are angered by seeing Jewish pain centered time and again now in mainstream media, while Palestinian suffering sees a fraction of the coverage. I’ll admit I’ve had these feelings, too. Being of the global majority, we are frustrated by one people’s struggles framed as the ultimate pain, under which other struggles and horrors are subsumed. Each time a Palestinian, who is already grieving immeasurable loss, is brought on a mainstream news program and asked “do you condemn Hamas?”, we feel their rage. The rage of being asked to dehumanize your own people, to erase your own sorrow, to accept that communities of colour are simply sacrificial lambs for Western interests and European guilt.

But I catch myself. Because I remember that this is how racism and imperialism works: it pits us against one another, so that we do its dirty work and capital benefits from our mutual destruction. Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman stocks had their best day in three years on October 9. Both are among the top contributors to political candidates and committees in America. When we turn against each other, the bloodbayers win. Because, ultimately, Israel and Palestine are both just pawns. Just as my own country, Taiwan, has always been a pawn.

To resist is to see the truth. So let us reject imperialist baiting to compare our suffering. Let us rise above white supremacy’s reductive and racist logic, asking us to prove who is Good and who is Evil. We must fight for what is right, not just for narrow conceptions of “our own”.

Let us struggle together to understand our intersecting histories of violence and oppression. Let us refuse attempts to reach for shallow, dogmatic simplicity—the warmongers’ favourite tactic. We must end these senseless cycles of pain and violence. It ends with us.

On remaining vigilant against attempts to dehumanize

The scale and range of efforts we are seeing to dehumanize Palestinians is breathtaking. And for those that benefit from Western empire and Israeli settler colonialism, their efforts are understandable—dehumanization is the only way to permit and rationalize the genocide unfolding in front of our eyes. If Hamas is seen purely as barbaric murderers, then Israel’s right to defend itself goes unquestioned. If Palestinians are not seen as human, there can’t be human rights violations—the 10,000 who have died to date are mere collateral damage.

There are egregious examples—such as Israeli President Isaac Herzog saying there are no innocent civilians in Gaza and Defence Minister Yoav Gallant’s comment that “we are fighting human animals”—but most insidious are the more subtle attempts at dehumanization. One example is the pernicious ways that establishment media describe institutions in Gaza as “Hamas-run”. Hamas has been the de facto governing body in the Gaza Strip since 2007, despite having the support of 27% of the population. As Mohammed El Kurd has pointed out, phrases like “Hamas-run schools” and “Hamas-run hospitals” are illogical—it’d be like saying “US-government-run hospitals”.

But this framing is not meant to be logical; it is meant to dehumanize the patients in these hospitals and the children in these schools, so as to preempt and prevent moral outrage when newborns die because hospitals have no electricity and Gaza becomes “a graveyard for children”.

President Biden has questioned the number of Palestinians who have died, saying “I have no notion if Palestinians are telling the truth about how many people are killed” without giving a reason for his doubt. This is despicable. International humanitarian agencies consider the figures from Gazan officials as broadly accurate and historically reliable. But even in death, America questions the humanity of Palestinians. In response, the Ministry of Health released a 212-page document containing the names and identity numbers of around 7,000 Palestinians; the WHO and other agencies confirm that there are still thousands buried under the rubble.

As Toni Morrison reminded us, the function of racism is distraction: “It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being.” Biden, the WHO, and the Gazan Ministry of Health all have more important work to do right now than engage in this ludicrous debate. But the longstanding dehumanization of Palestinians keeps our energy on the wrong questions. Questions like “can we trust the death tolls from Gaza”, not “how do we stop the killing immediately?” Or “why are Hamas such barbarians”, instead of “what conditions led to such desperation on their part?” Or “what does this crisis mean for Biden’s electoral prospects in 2024”, when the real question is “how do we right these grave injustices that have continued for 75 years?”

We must critically question cultural narratives, and how labels such as “terrorist” are being wielded. During the Cold War, the US government deemed South Africa’s African National Congress a terrorist group. Nelson Mandela remained on the US terrorism watch list until 2008. So better questions might be: How has “terrorist” been historically weaponized to erase legitimate grievances and dismiss inevitable responses to generations of oppression? People are not born terrorists, so why might some feel the need to resort to extreme violence? (I always find literature unparalleled for understanding multifaceted social and human layers. Some ideas: The Book of Gaza, Time of White Horses, Light in Gaza, and Mornings in Jenin. For a short video, here is El Kurd on the neverending Nakba.)

At the National March on Washington on Nov 4, where an estimated 300,000 people marched in support of Palestinian liberation and to demand an immediate ceasefire, I saw dozens of people carrying a scroll. I walked up and realized it was the name of all Palestinians that have been killed to date. The scroll was dense with small script printed across three columns, and still, from where I stood, I could see neither its beginning nor end. Walking along the scroll, I read as many names as I could. I tried to imagine who these humans were, what their lives were like, what they loved to eat, how they liked to dance. I wondered why I got to be born into this body, one that is safe, one reading rather than being on this list of martyrs. I wondered why I got to be in this body rather than a Palestinian body, a body elite powers deemed unworthy of care, a body still trapped under a building and thus not honoured on this scroll, a body that is now a name among endless names being used to shame those who are not shamable.

I watched one of the women carrying the scroll. She was about my age, perhaps a little older. Her face was locked in steely anguish as she stared at the names, lost in thought. She then looked up and saw my gaze. I instinctively turned away, embarrassed to have been caught staring, but when I turned back, she was still looking at me. We locked eyes and tears rolled down both our faces. We didn’t exchange a word.

In these times, we must bear testimony and connect with each other—this is where I often turn to art. I turn to art to create spaces where we can suspend sociopathic realities, hold each other, and topple lies. (I recognize this might sound naive today, but I’ve written about the history of US Cold War propaganda that played a pivotal role in shaping the dominant apolitical, art-as-object version of the art world we see today. Despite this history, I believe another path is possible.)

And yet, many American arts and cultural institutions typically vocal about collective liberation seem to be hiding under “it’s too complex” and staying silent. Others are bucking under pressures to distance themselves or even punish artists that speak out for Palestinian liberation. 92NY canceled a talk by Viet Thanh Nguyen after he signed an open letter condemning Israel's indiscriminate violence in Gaza. (In protest, writers and critics Christina Sharpe, Saidiya Hartman, Dionne Brand, Paisley Rekdal, and Andrea Long Chu all canceled their appearances.) Collectors and galleries are threatening artists who have shown public support for Palestine, whether through signing open letters—Artforum fired its editor for doing so—or simply liking sympathetic social media posts.

This pattern is especially alarming when it comes from those who pride themselves on championing historically marginalized groups. El Museo de Barrio removed an artwork displaying the Palestinian flag from an exhibition. The artists, Roy Baizan and Odalys Burgoa, had refused to bow to the museum’s objection to the inclusion of the flag, as they saw it as integral to a work about political resistance and commemorating the dead. For cultural institutions that claim to support freedom of speech and political transformation, the math isn’t mathing.

If this Jewish mother, whose son was killed in a Hamas attack, can plead for an end to the war, what right do the rest of us have to hide behind complexity? If after experiencing such shattering loss, she can reject the propaganda of the Israeli far right, then how could we accept it? This grieving mother is absolute in her moral clarity: ”in my name, I want no vengeance”. Institutions built on championing justice and liberation would do well to learn from her.

So let us stand against the coordinated dehumanization of Palestians. Let us fight any attempts to erode the sanctity of any human life. In many ways, it is not about being magnanimous; this vigilance, in fact, is quite selfish. For we are not just defending the humanity of any one group, we are preserving our own humanity as well.

On narrative organizing when mainstream discourse is so captured

We are outraged. Our leaders are failing us, establishment media is engaged in structural gaslighting and dangerously sloppy reporting, and we feel impotent as mass murder unfolds in front of our eyes. As a result, many of us have turned to social media to repudiate the farcical mainstream analyses. As we scroll, share, like, and repost, the collective feeling seems to simply be: make it make sense. As my friend Baratunde Thurston noted, this is not just a physical war, it is also an information war, one playing out daily in our social media feeds. “In this context, we are all involved—both as witnesses and combatants—lobbing links, videos, and text screeds onto the digital battlefield.”

I’m guilty of this. Over the last year, I’ve worked hard to develop intentional information habits: immersing myself in delicious, meandering face-to-face conversations instead of scrolling through hot takes, consistently reaching for physical books instead of online posts. The past month destroyed that. But given the capture of establishment media, where else can I get information? And from a narrative organizing perspective, how do we counterbalance and hold mass media accountable?

A good start is getting updates directly from affected communities. Some journalists and Gaza-based accounts on Instagram are Motaz Azaiza, Plestia Alaqad, Ahmed Hijazi, Mohammed Majed Aborjela, and Yousef Mema. Given their courage and tenacity in doing this work under impossible circumstances, the least we can do is listen. We must also be vigilant in monitoring and holding the media accountable. Folks like Sana Saeed, Ahmed Eldin, Subhi Taha, and Salma Shawa are doing important work to counter bias, propaganda, and misinformation, let us learn from them.

Photojournalist Asim Rafiqui articulated why it is important to be on social media right now:

“We are here because the Palestinians are here. It is here that the news is being broadcast, and truth posted by those who are erased by mainstream media. It is the Palestinians of Gaza that pulled us here. Those not sharing, writing, speaking are breaking a chain of connections the Gazans have worked to create. It is they who have faith in us and that we will see, and we will speak, and we will add a chain to this link.

When you don’t repost, share, add your voice, when you just leave the post unanswered, unresponded to, you are breaking this tapestry, this beautiful solidarity. We are here on social media because the Gazans brought us here.

It is not performative. It is not righteous. It is an answer to a desperate people who reach out every day and show us their dead children, their murdered families, so that everyone can see through the lies of the powerful. We are here because we have a responsibility to live up to their faith in us.”

His words resonate with me, though I believe there are multiple ways to bear witness and to support, e.g. by reading books, attending protests, donating money, having hard conversations, and joining movements led or endorsed by those most affected. Especially for those of us who are empaths, we must check in with our nervous systems and find ways to resource ourselves. For being overwhelmed and debilitated by grief benefits the oppressors. So how to continue to bear witness and share what is happening, as affected communities ask us to, without letting it paralyze us? The answer for each of us will be different.

While social media is incredibly important right now, we must also remember its limitations. It is but a starting point for political education and for plugging into broader efforts—we must carry that energy beyond the screen. Social media also flattens nuance and incentivizes the most incendiary rhetoric. We know this, yet we remain glued to our phones, scrolling and sobbing, litigating history, cosplaying diplomats, and debating in DMs late into the night. Is it helping? Are we changing minds and improving lives, or are we just yelling into an echo chamber of outrage? This thread from Derecka Purnell, describing an encounter at Busboys and Poets in DC, reminds us of the necessity of face-to-face dialogue.

We must also reflect critically on why Palestine and Israel have captured so much attention, while other “silent genocides” continue with limited outcry. An estimated 9,000 people have been killed and another 5.6 million displaced in the war in Sudan, now in its seventh month. Conflict and escalating violence has uprooted 6.9 million people in the Congo; in one displacement camp, 70 sexual assault victims per day seek help at Médecins Sans Frontières clinics. Approximately 1.7 million Afghans are facing deportation from Pakistan. There are active crises and conflicts in Burkina Faso, Haiti, Mali, Niger, and Ukraine. Most of these countries are among the poorest in the world, where Western capital has either comparatively limited interests or can already operate freely with impunity.

But Israel? Since World War II, Israel has been the largest cumulative recipient of US foreign aid. (In 2020 alone, the US gave it $3.8 billion in aid, and only $19 million to occupied Palestine. Is the worth of a Palestinian life truly 200 times less?) America needs a foothold in the region to maintain its access to oil, and Israel helps crush movements to nationalize resources. From serving as a Western-funded tool to attack Egypt and Syria in the 1960s, to doing US dirty work now by sending weapons to Nicaragua, Guatemala, Philippines, and more, the US-Israel bond is special indeed. Pro-Israel interest groups, for their part, donate millions to US politicians to maintain the unshakeable relationship. During the 2020 campaign, pro-Israel groups donated approximately $33 million to federal candidates.

In the face of such entrenched and money interests, how do we move? This is not my field of expertise, so I look to experts like MediaJustice and its founder Malkia Devich-Cyril, and the campaigns they point us toward. What I do know is we must be critical readers of the media, especially as actors like Israel’s foreign ministry spends millions on YouTube ads and groups like the Israeli American council buy out billboards in Times Square. And we need more monitoring of media bias, and calling out of media complicity enabling genocide and structural violence.

The fact that so many institutions are threatened by narratives about Palestine and lashing out at those advocating for Palestinian rights, shows the power and strength of our movements for truth. “There is an increase in people who are really concerned with the genocidal intentions of Israel right now—and they’re being met with immense McCarthyite backlash and suppression,” said Radhika Sainath with Palestine Legal (please donate to them!). “The repression we’re seeing is different in nature and more intense than anything we have witnessed in recent years.” Despite great personal risk, people of conscience, especially young people, are speaking out.

Because they are speaking out, we are seeing the edifice crumble.

Part 3: Closing Reflections

When I started this post, I felt like I wouldn’t be able to find the words to articulate what I am moving through in this moment. 6,000 words later, I still don’t think I’ve found the right words. But I came to the page, where I begin all my processing, because I was struggling to make sense of what I had experienced on my travels. Because in conversations with Palestinian and Jewish friends, I saw how both were feeling equally dehumanized, erased, unsafe, and despondent. Many, especially Palestinians, told me how nervous they are about speaking out now, for fear for their physical and economic security—would I please continue to do so? The Jewish left is now deeply divided—as a mediator, did I have any thoughts on how to come together? I don’t know.

But I know what I do see: immense pain on all sides, and limited constructive outlets for processing it. We need these outlets. Desperately.

My family’s history has been defined by foreign occupation, by war, by migration, and our history informs how I think about what is happening now. My search for pathways to heal from dark histories have brought me to work on repair and reparations, deliberative democracy, truth and reconciliation, and transitional justice.

But I don’t pretend to understand what this moment is like for Palestinian, Jewish, and Arab communities in the region and across the diaspora. I don’t pretend to understand the immense pain—historical, ancestral, soul-deep—that this has excavated, and that continues to play out daily. But as someone who holds spaces for difficult conversations across deep divisions, I’m reflecting on what we can learn from this moment. The questions I am holding:

How do we create spaces to come together that are capacious, that invite us to hold multiple truths, and that help us turn toward each other’s tender humanity and pain?

Who is trusted to hold which spaces, and for whom? How does that shift across issues, communities, and contexts?

What are ways we can hold one another—with compassion and across differences—as we struggle together toward a world rooted in radical love?

I’d love to hear about resources, spaces, and actors working on these questions.

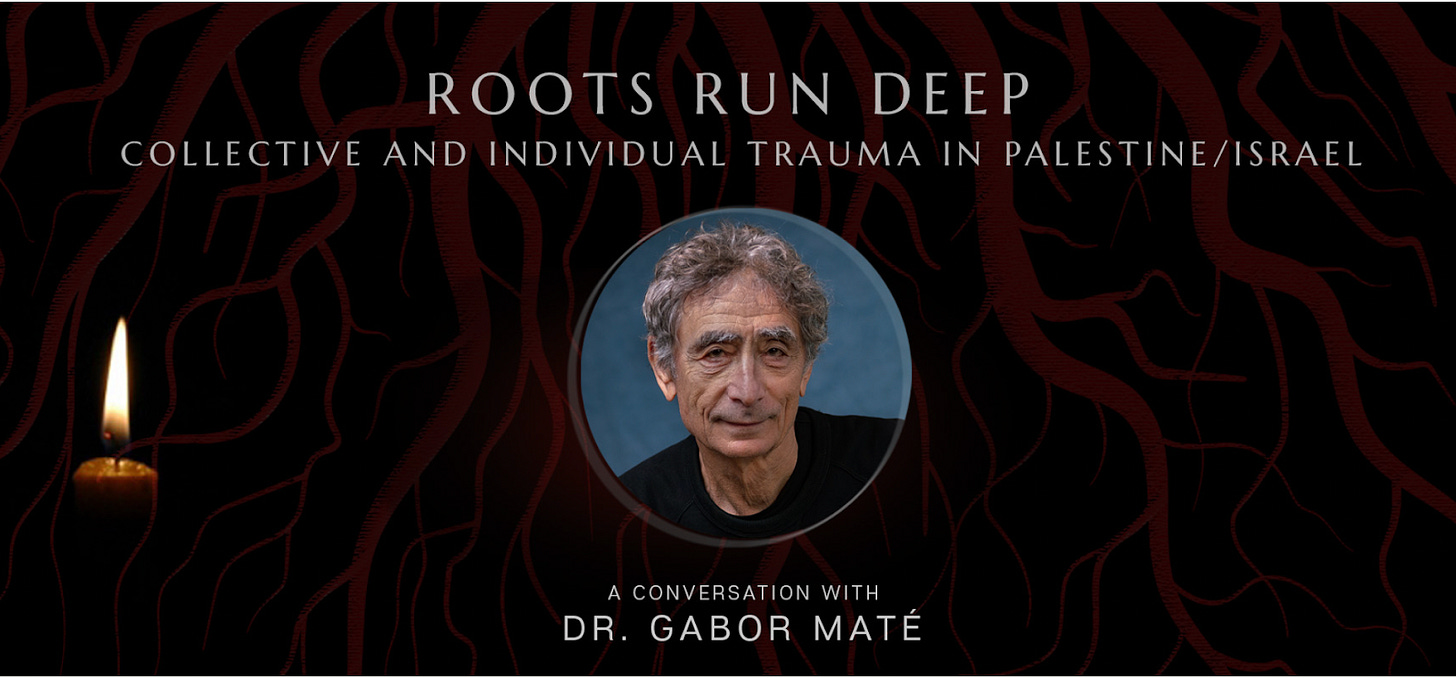

In closing, I want to point toward the best answer I have found in recent weeks in response to these questions. It was a session I attended on collective trauma in Palestine and Israel, featuring Dr Gabor Maté. Maté is a Holocaust survivor whose grandparents were killed in Auschwitz. He became a Zionist because he believed in “this dream of the Jewish people resurrected in their historical homeland, and the barbed wire of Auschwitz being replaced by the boundaries of a Jewish state with a powerful army”. It was only later in life that he understood the waking nightmare required to maintain the Zionist dream. In his talk, Maté speaks of the deep pain he feels as a Jew, while being unequivocal in condemning Israel’s maniacal violence towards Palestinians.

The whole session is worth watching, but what struck me most was an exchange between Maté and a woman named Karen. (Starts around 37:00.) Like Maté, Karen’s mother was a childhood Holocaust survivor, and believes that he has internalized self-hatred. Karen is upset at Maté for not “standing up against barbarity” and for betraying his people. She believes that now is not the time to be critical of Zionism; rather, we need to “wait until people feel safe and secure”.

Maté’s response moved me—both the content of his words, and how he simultaneously holds Karen’s pain and his truth. He shared how he came to choose authenticity to himself over acceptance by others, including students who have since denounced him. It was a masterclass in how to acknowledge and hold multiple truths, and to do so with compassion and conviction.

May we find and create more of these spaces, and may they multiply, so that our communities and our institutions—from the micro to the macro—reflect who we really are: Interconnected beings who can simultaneously feel pain and choose love, whose soul-mind-body-hearts stand with life and yearn for liberation.

For Further Rumination

A set of resources I have found helpful, some of which are linked in the post:

“A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation”, by Fady Joudah. I don’t know how to sum up this piece, so just please read it.

Ganavya’s music has been medicine in this time, and this song in particular has been a balm for me—as prayer, practice, incantation.

Collective & Individual Trauma in Palestine/Israel with Dr. Gabor Maté, from Science and Nonduality; as I mentioned, the whole thing is worth watching but especially his Q&A starting at 37:00.

But We Must Speak: On Palestine & The Mandates of Conscience, from the Palestine Festival of Literature; I appreciated all of it but especially the conversation between Rashid Khalidi and Ta-Nehisi Coates, moderated by Michelle Alexander (27:45)

“The Violence of Demanding Perfect Victims” by Noura Erakat on immoral, hypocritical Western demands: “The problem is not the Palestinian people’s insatiable thirst for freedom but an international status quo that has aimed to normalize Israel’s permanent subjugation of Palestinians.”

“When ‘Never Again’ Becomes a War Cry”, by Natasha Roth-Rowland, on how the dangerous and disingenuous “Holocaustization” of the current crisis.

“Western Journalists Have Palestinian Blood on Their Hands”, by Mohammed El Kurd on how mainstream media’s relentless dehumanization of Palestinians is enabling Israeli war crimes.

“When Hurt People Hurt People”, by my friend Micah Sifry on the paradox of being powerful and feeling powerless; how the Israel-Hamas war is polarizing Americans; and the possibility of a different path.

“Coming Out of the Palestinian Closet”, by Siham Inshassi, which captures the fear and pain that some Palestinian friends have shared in this time.

“My Lonely Search for a Jewish Community that Lives its Values”, by my friend Erin Mazursky on her journey with her Jewish identity and how to hold complexity and challenge hypocrisy in this time.

The resignation letter from Craig Mokhiber, former Director of the New York Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. It is worth reading in full.

“History in Copresence: Creating a Multidirectional Memory of the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization”, an interview with memory studies scholar Michael Rothberg.

Wow Panthea, thank you so much for writing this piece. I'll be sharing it in my Monthly Digest this weekend. Welcome to Substack! 🧡

Thank you for the resources and the space to reflect.